Opportunity Hoarding at Rutgers

By Keith Green

On Monday, April 11, Rutgers-Camden hosted its inaugural Chancellor’s Lecture on Global Racial Reckoning and Civility with Professor Sheryll D. Cashin, Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Law, Civil Rights, and Social Justice at Georgetown Law. Cashin used her latest book, White Space, Black Hood: Opportunity Hoarding and Segregation in the Age of Inequity, as a point of departure for considering these weighty issues, and her illuminating presentation was well received by the wall-to-wall audience in Camden’s multi-purpose room.

Although Cashin’s analysis was focused on economically impoverished Black and Brown communities in cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Chicago, her insights are also useful for thinking about the abject position of Rutgers-Camden within the larger Rutgers University system.

The core of Cashin’s argument is that three techniques are responsible for the concentration of poverty in modern U.S. cities: opportunity hoarding, boundary maintenance, and surveillance.

Opportunity hoarding means overinvestment in some spaces and disinvestment in others—that is, spending millions of dollars in certain neighborhoods, downtowns, and school districts while bypassing others, thereby creating conditions of affluence and poverty that appear self-evident and inevitable when they are, in fact, controllable. Boundary maintenance means preserving the conditions created by hoarding, ensuring that the distinctions between communities are preserved and the privileged retain their elite status.

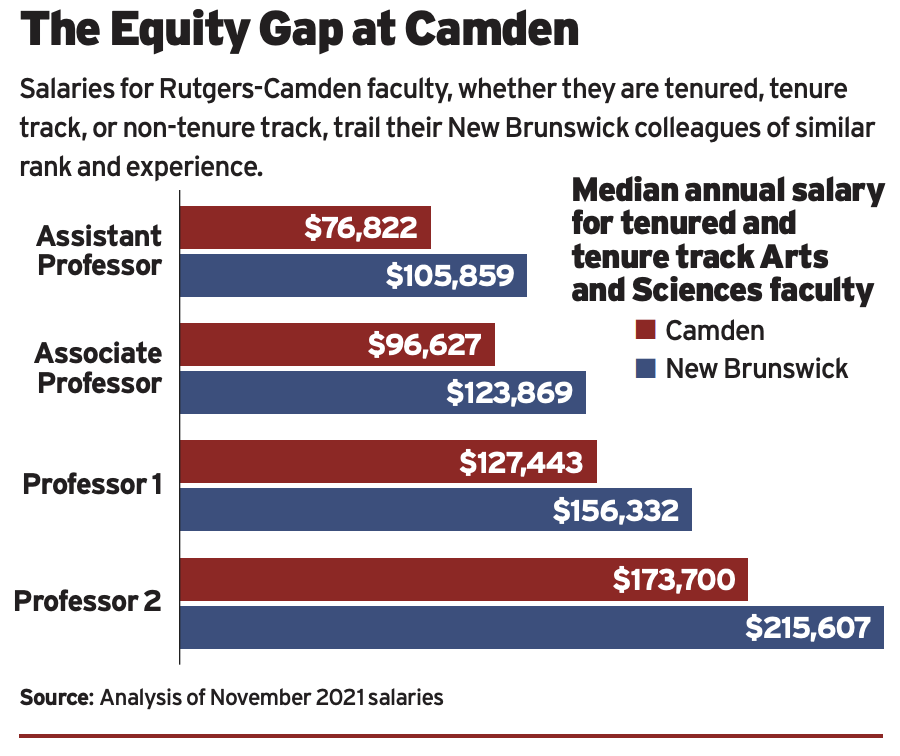

To the students, staff, and faculty of Rutgers-Camden, these first two modes of disenfranchisement sound eerily familiar. Indeed, the phrases “opportunity hoarding” and “boundary maintenance” could well serve as captions for any side-by-side comparison of the resources available to students, staff, and faculty at Rutgers-New Brunswick and other parts of the Rutgers system. Whether we consider investments in dorms, classrooms, course variety, student services, staff or faculty pay, it’s clear that Camden and Newark don’t hold a candle next to the high intensity, football stadium lights of New Brunswick.

If Rutgers wants to “reckon” with this inequity, it would do well to take a page from Cashin’s book. She writes that the most effective way to combat inequity is to “invest resources and transfer assets.” (207) Those are fighting words. Rutgers likes to claim it’s revolutionary, but it can only pay lip service to the kind of redistribution of resources for which White Space, Black Hood is calling. How revolutionary would it be for Rutgers to house students in Camden according to the standards of dorms in New Brunswick? How revolutionary would it be for Rutgers to compensate staff and faculty in Camden the way it compensates staff and faculty in other parts of the Rutgers system?

Cashin’s inspiring lecture was the first of many to come on the theme of Global Racial Reckoning and Civility. The lecture series is timely and welcome. However, Rutgers needs to honor Cashin’s work and analysis by seriously investing in the Camden campus and giving it the resources it needs.