Stadiums on Strike: Arena Staff Demand Benefits and Better Pay

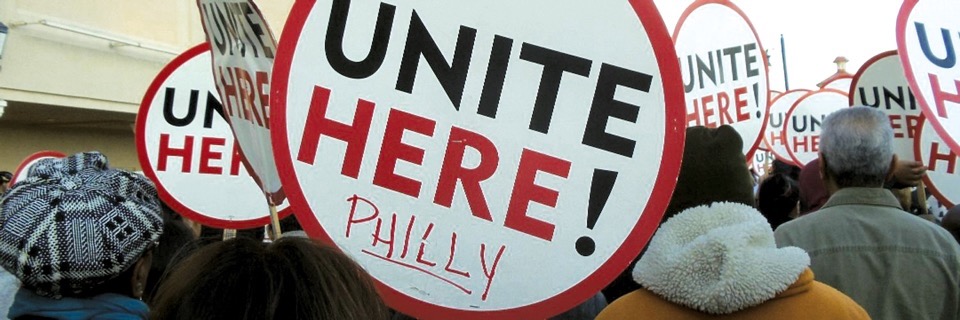

UNITE HERE Local 274 is one of the top unions in Philadelphia and the top food service union in the city, representing 4,000 workers in the private sector (hotels, stadiums, universities, and cafeterias) and an additional 2,200 working in the public sector for Philadelphia’s public school system, according to their website.

One of their top employers, Aramark, reported an $18 billion revenue in 2023 and sells food and drinks at the stadiums for a premium, with some alcoholic beverages costing up to $18. Despite this, their lowest-paid staff members make as low as $10 an hour. A combination of this and other factors, such as healthcare, prompted the union to call a strike beginning on September 23rd.

“Striking is typically thought of as the highest form of collective action,” says Rutgers University–Camden Professor of Philosophy, Austin Rooney. In his view, it’s the final step in the bargaining process–“you’ve attempted to negotiate in good faith, you’ve attempted to demonstrate to management that you have the power and the resources to negotiate what you consider to be a fair contract, and that your demands need to be met.” Rooney has personal experience with striking and organized labor–he serves as the vice president of the adjunct faculty union at Rutgers–Camden, and was involved in their strike in the Spring of 2023 and the subsequent contract negotiation process.

One of the greatest aims of a strike is to prove the “value of […] labor…and raising awareness” for the cause, Rooney says. In some cases, when good faith negotiation fails, it becomes essential to “withhold labor” and go on strike. The success of a strike depends on a variety of factors, according to Rooney. Sympathy from the public is one such factor, as unions have to consider if “the local community [will] view th[e] strike symapathetically,” and even if the press will cover the strike in a sympathetic manner. On the government side, it is also important to consider how “the legislature will view th[e] strike.” In this regard, it is important for unions to get the timing of their strikes just right and to try to control the narrative around said strikes–as Rooney points out, “there are certainly strikes that just end with the Union being decimated, and so its certainly not something that should be taken lightly.” Since striking is the last step, “you have to [count] your paces all the way there,” and focus on getting it right.

In videos released by UNITE HERE Local 274 on their website and social media channels, workers outline the issues that are prompting them to strike–over and over again they emphasize the need for healthcare benefits and competitive, living wages. It is in the contract negotiation process that things such as that get sorted out, Rooney says. “Both management and labor will have to name a lead negotiator, and that person […] is responsible for scheduling negotiation dates, and they […] go from there in terms of the agenda, and of what that they can achieve.” Often, the process is centered around wage negotiation, but a common strategy “is to deal with the little stuff first.” This can be anything from working hours to working conditions, and things like healthcare come into play then as well. The negotiation process can take a long time, as can strikes–the Rutgers Faculty were on strike for five days, and the Aramark workers for four, but some strikes can last weeks.

Union leadership has called the strike off temporarily in (slightly overblown) anticipation of a Philadelphia Phillies postseason and has not reinstated it. Still, their website warns members to be on the lookout–saying, “A strike could be called at any time!”